Hyla Stories

The Power of Words

Connecting language and action in middle school and beyond:

The growth from 6th to 8th grade is tremendous. While the physical changes are most obvious, academic and personal growth is also profound during these years. As students assert their identities with more and more maturity and independence, the language they use evolves with them. They use it to express who they are, and also to connect with others – and it takes practice. Communication is at the core of Human Relations, and teacher Cooper explains that language is “at its best, how we express our emotions, deepen understanding, and build connections and trust with others.” Language is an essential tool for personal growth and being in community. Knowing this, we help students develop fluency and familiarity with the language that equips them to respectfully participate in diverse settings.

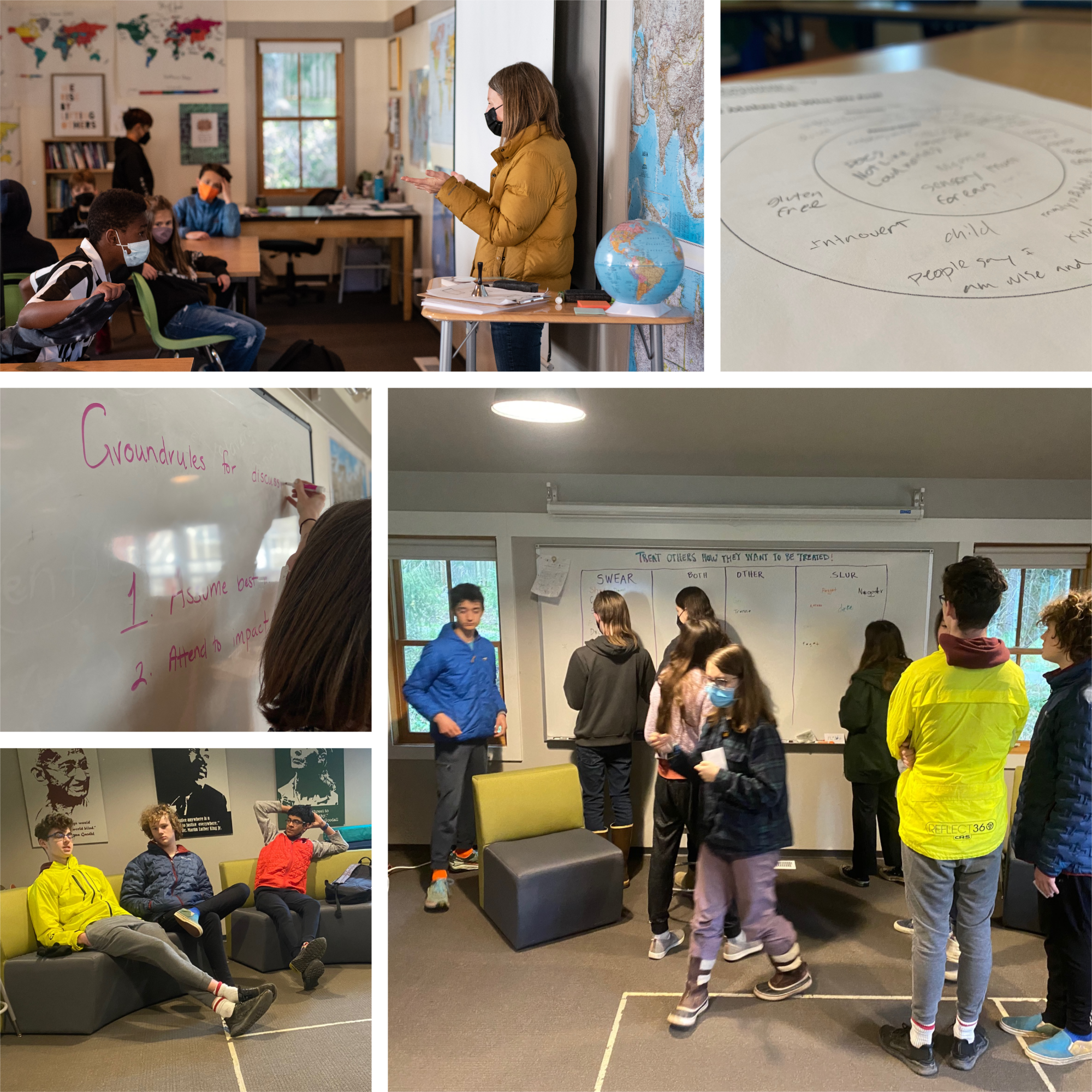

During a Human Relations workshop focused on the power behind certain words, students explored different categories of language: slurs/swearing (and the difference between them); words that push the boundaries of specific audiences; and words that are totally off limits. With help from the 8th grade Allies Club leadership team (an Elective with Alex), students then looked at specific words and sorted them into the categories where they belong. “This prompted some deep conversation and questions around context, identity, and perspective,” shared Cooper. “Our goal has been to help build understanding and agreements over the power of the words we choose, and to have the context to say what we mean with consideration and care for others.”

This workshop echoes some of the main themes of the anti-bias studies happening a few doors down in Global Ed class where students work to build racial literacy with a curriculum from Learning for Justice, a pioneering anti-bias education program developed in 1991 that provides content and resources for educators and families. The framework begins with identity. “The first thing I want students to do,” says Deborah, “is really situate themselves. So we’ve been talking about how identity is a combination of social identity visible on the outside, like our race, age, and gender, and personal identity – what we know to be true about ourselves. We talk about how these identities interact to determine how we move about the world and experience it.” Deborah begins by using herself as an example, asking students to name her social identities. “It took a while to get to the obvious fact that I am white. We have a tendency to tiptoe around race and use color blind language, and the problem with that approach is that you brush over important and distinct differences in how people are treated and how they experience the world.” Then, students explore the concentric circles of their own identities: personal identities – such as being a gamer – and social markers, like being male, white, and Jewish, for example. This allows students to think about how others might respond differently to these different identities in different settings. Deborah explains: “this is how students begin to understand how social markers like race and gender, and not just personal identities, like values, attitudes, and interests, impact their experiences.”

After identity they look at diversity, which “builds empathy,” says Deborah, “and the recognition that there are a variety of experiences, and the awareness that your own personal experience is not necessarily universal.” Next students move into justice, an area that “recognizes there are very real and unfair differences in how people experience the world based on their social identities. This allows us to go beyond awareness to really understand privilege, oppression, and patterns of inequality.” Deborah explains that for 6th graders this stage includes a lot of discussion about fairness, while 7th and 8th graders look at structural inequality, historical events, and institutional patterns and the impact of discriminatory policies. The program concludes with a focus on action.

As they progress through the program, students develop familiarity with new language and a common understanding of words that allow them to have meaningful conversations. “I want this to be a safe space where students aren’t afraid to ask questions or express ignorance when they are genuinely reaching out to understand.” To build that environment, the whole program begins with agreements around group discussions: (1) Assume best intent; and (2) attend to impact. “We spent a lot of time on the first agreement, and students decided it was important to give people the benefit of the doubt and also some space and understanding as we realize that we don’t yet all have the vocabulary.” The second agreement is about taking ownership for the impact of your words, even if the impact is not what you intended. “This is all about equipping them with language,” Deborah explains, “so they can approach that moment of disconnect, acknowledge someone’s reaction – and also acknowledge that wasn’t their intention – and then move beyond that disconnect to reach understanding and create more connection.”

For Deborah, racial literacy also helps students place themselves within larger contexts. “I come at this as a sociologist. We are always interested in the interactions between the individual and the larger social structure. So that’s inherent in my thinking and my teaching. Beyond compassion and empathy, this is also about recognizing that we are products of the environments we’re part of – and so is everyone else.” Ultimately, this is the work of global citizenship. We seek to understand how we operate in the world, how others operate, and grapple with the social responsibilities we have to ourselves and our communities, both local and global.”

Next students will welcome a visitor, Peter Berner-Hays (our Interim Assistant Head of School) who will share the story of why he has two passports. He’ll tell students about his family’s Jewish heritage their experience in the Holocaust, and talk about how his family history does and doesn’t shape his own sense of identity today.